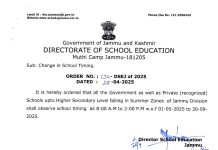

Lt Gen HS Panag

The year was 1954, 17 Sikh was located at Agra and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Shamsher Singh, whose outstanding leadership and exploits in the 1947-48 war in Jammu and Kashmir were part of regimental lore. The unit was out on a training camp in a forest near Shivpuri, which was to culminate in a test exercise.

One day, Sepoy Fauja Singh, who was part of the officer’s mess staff, went to collect firewood for the mess kitchen. Suddenly, a tigress jumped out from a thicket and pounced on him. Instinctively, he tried to fight her off with his bare hands. After a brief struggle, the tigress caught Fauja Singh’s turban in her mouth and thinking that she had got the kill, disappeared back into the thicket. Fauja Singh was badly mauled and he was evacuated to the military hospital immediately, but more to the point, he was extremely upset about the loss of his turban.

More reports poured in about the tigress with four cubs, who had turned into a man-eater, it seemed. She had killed two persons from a village nearby. True to the Indian Army tradition, this didn’t stop the training, which continued as per plan, and the test exercise was cleared with honours.

At the end of the exercise Lt Col Shamsher Singh proposed to his Brigade Commander, Brigadier Danny Misra, that since the tigress had turned into a man-eater and the area was used by the brigade for training, it would be prudent to kill the tigress. Back in those days, shikar was allowed in the country and a hobby for some. In that spirit, Brig Danny Misra agreed to the proposal, but with a rider. “Shamsher,” he said. “Killing a tiger with rifles is too easy. Can the Sikhs do it with bayonets?” Never one to shy away from a challenge, Singh said, “So shall it be, Sir!”

The die was cast. Shamsher returned and briefed his unit. He pepped his soldiers up by telling them stories of how Hari Singh Nalwa, commander-in-chief of the Sikh Khalsa army, had once killed a tiger with his bare hands by catching hold of its tongue and choking it.

It was decided that the unit would assault the general area where the tigress was suspected to have hidden in traditional infantry manner. Once the tigress attacked an individual, he must use the bayonet to counter attack it while the personnel on his flanks would turn inwards to attack the tigress with bayonets and finish the task. This drill was rehearsed to perfection. Next morning, two companies of 17 Sikh formed an assault line 200 yards long, with the Commanding Officer’s party in the centre. Bayonets were fixed on the Enfield .303 rifles and the assault commenced.

It was a surreal scene: bayonets glinted in the morning sun with soldiers of 17 Sikh shouting “Jo bole so nihal!”, out to kill a man-eating tigress with only bayonets! On the far side of the suspected area, the Divisional Commander, General Dargalkar, and the Brig Danny Misra, sat on a machan with sporting rifles. Misra didn’t believe the tigress could be killed with bayonets. His plan was that the assault by 17 Sikh would drive the tigress towards the machan, where Gen Dargalkar and he would kill her.

The movement of the assault line was laborious due to the broken terrain but after 20 minutes, the den of the tigress was located. She had fled, but her three cubs were found, captured alive and later presented to the Agra zoo. Fauja Singh’s turban was also found in the den.

The assault line formed again and moved forward with regimental war cry. After 10 minutes, the roar of the tigress was heard. Singh shouted to his boys, “Tagde ho jao!” (“Gird up and get ready for action!”). And then, suddenly, the tigress leapt out of the thicket and attacked the assault line. Sepoy Sucha Singh was directly in front and he adopted the traditional bayonet fighting stance, meeting the tigress’ assault head on with his weapon. As she came at him, he plunged his bayonet into her chest. It got buried to the hilt, inside the tigress’ chest, but the momentum of her charge knocked Sucha Singh down. With the momentum, the tigress fell 10 yards forward. As per the rehearsed drill, the soldiers on the flanks turned inwards and pounced on the tigress, pinning her down with their bayonets. It wasn’t necessary. Sucha Singh’s bayonet had already pierced her heart.

It was then that the sound of a rifle shot was heard. Shamsher was livid with anger, thinking one of his men had disobeyed orders. He rushed to the scene and asked who had fired the shot. The soldiers assured him no shot had been fired and the report had come from the direction of the machan. Shamsher ordered the success signal be fired with the Very Light Pistol and 500 hundred voices joined him in the long jaikaraof “Jo bole so nihal!‘.

Then Shamsher rushed to Sucha Singh, who was badly mauled, but on inquiry about his wounds said, “Saab ji main tan theek haan, par woh sali sherni meri rifle lai gayee.” (“Sir, I am ok but the damn tigress has taken off with my rifle”). The loss of a weapon is a very serious lapse in the army! Sucha Singh was assured that the rifle has been recovered and that he was now nearly at par with the great Hari Singh Nalwa for having single-handedly killed a tigress. He was evacuated to the military hospital.

A telegram was despatched to Fauja Singh: “Revenge taken! Tigress killed! Turban recovered!” Sepoy Sucha Singh was immediately promoted to Lance Naik and on that day, 17 Sikh was rechristened the Tiger Battalion.

The bayonet of Sucha Singh had developed a 10-degree curve due to the force of the impact with the tigress. A most unusual occurrence, as bayonets are usually made of brittle metal designed to pierce and break when it hits a hard surface. Shamsher directed that Sucha Singh’s bayonet must be kept as a trophy. The Quarter Master in his enthusiasm to get Sucha Singh his replacement mistakenly sent the bayonet back to the ordnance depot for replacement. Fortunately, it was located and brought right back to the unit. The bayonet, along with the skin of the tigress and news paper coverage of the event, still adorn the officers’ mess of 17 Sikh — The Tiger Battalion.

While Sucha Singh was being taken to the military military hospital, Shamsher went to the machan to report the success of the mission to Misra and Dargalkar, who were still on the machan. To his amusement and the embarrassment of the VIPs, Shamsher learnt that in the excitement of the whole action, one of the rifles from the VIP machan had accidentally got fired. That was the rifle shot Shamsher had heard!

Later, Misra along with Shamsher went to meet Sucha Singh in the hospital. The brigadier asked Sucha Singh, “Kya aapne hi sherni ko mara tha?” (“Are you the one who killed the tigress?”) A peeved Sucha Singh replied, “Asli bayonet toh mainne hi mara tha, sir, par mari hui sherni par bad mein aur bhi maarte gaye. Aur mainne suna ki dar ke mare VIP machan se, kisi rifle nichhe gir kar fire ho gayee.” (“I’m the one who got her with the bayonet first, but others attacked the dead tigress too. And I heard that up in the VIPmachan, someone got so scared that he dropped his rifle by mistake and fired it.”)

Nine years later, Colonel Shamsher as the Centre Commandant of the Sikh Regimental Centre at Meerut Cantonment, was interviewing soldiers going on pension when he heard the familiar voice of Havaldar Sucha Singh. He reported that he was going on pension. Shamsher took a quick decision and directed the pension orders to be cancelled. Instead, Sucha Singh was promoted to the rank of Jemadar. There were objections from higher headquarters, but Shamsher had a simple reply: “Sucha Singh is probably the only man in history to have killed a tigress with a bayonet. He deserves to be a JCO!”

I was six years old, living in Agra Cantonment, when all this happened. I remember when the Commanding Officer’s jeep came back from the exercise, spread across the bonnet, was the tigress, and it seemed like all of Agra was lined up on Mall Road, to welcome the unit.

But the story with all its details and glory was told to me by someone who was there and had seen the whole thing: Colonel Shamsher Singh, my father.